Amy Crompton (Systematic Review Analyst) and Tom Macmillan (Consultant - Systematic Review)

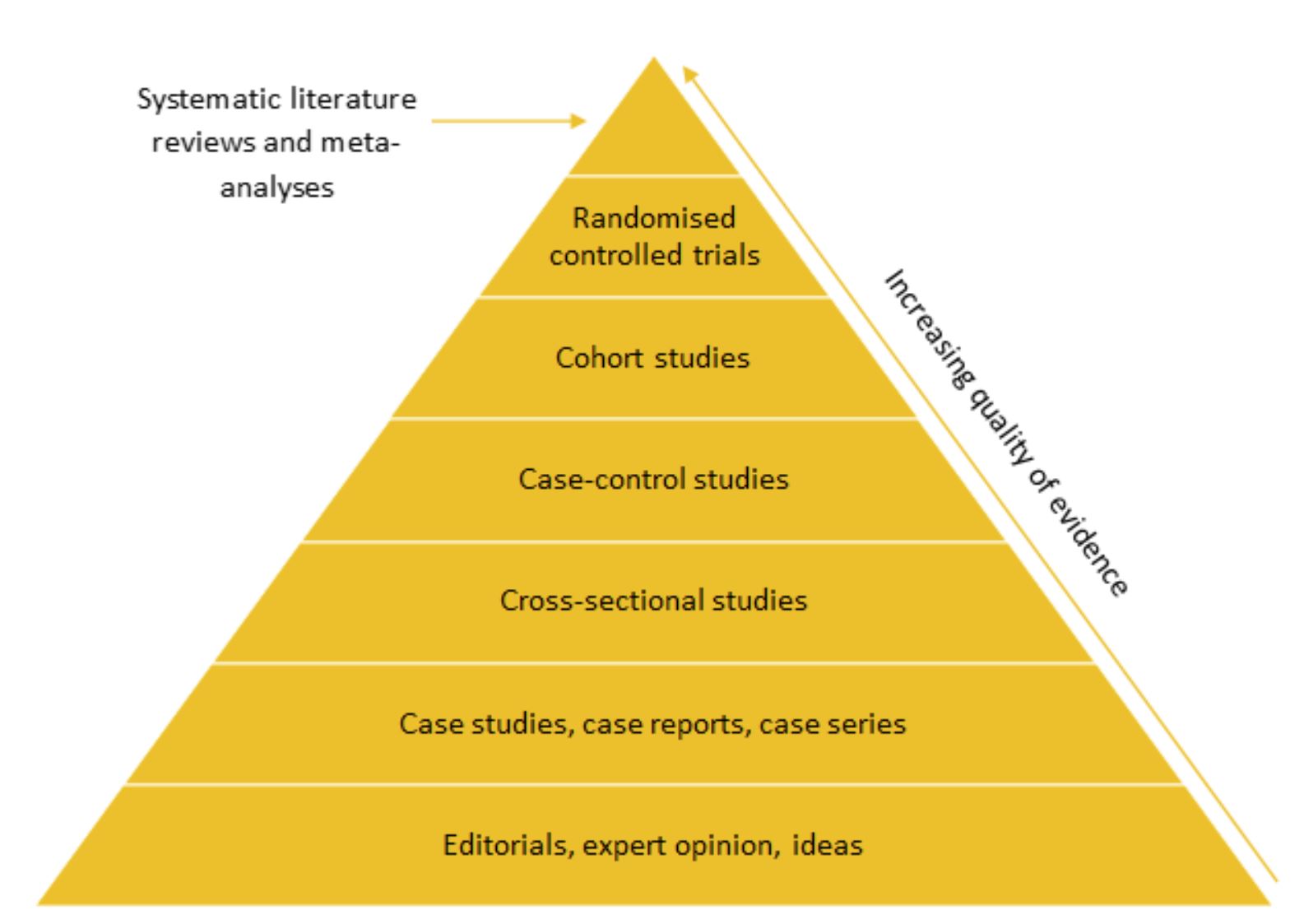

Hierarchy of evidence

Different study designs are often ranked in a hierarchy of evidence based on their validity and robustness. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are typically considered the gold standard source of evidence, however systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses sometimes appear at the top of the hierarchy.

Randomised controlled trials of medical devices

Randomised controlled trials are often resource-intensive, expensive, and may not always be the most appropriate study design (1). An RCT can take several years to complete, at which point another medical device may have been proven more effective (2). Additionally, it may be unethical to assign patients to an untreated control group, and blinding is not always possible in the assessment of medical devices. The evidence for medical devices is therefore often limited to non-randomised studies only.

Value and application of real-world evidence

Real-world evidence (RWE) can provide valuable insights into the benefits and negative sequalae of healthcare interventions. Real-world clinical and economic data, patient-reported outcomes, and health-related quality of life data (3) can support both the clinical and economic evidence base for medical devices.

“The popular belief that only RCTs produce trustworthy results and that observational studies are misleading does a disservice to patient care, clinical investigation, and the education of health care professionals” – John Concato, M.D., M.P.H. (4).

The value of RWE is increasingly being recognised by health technology assessment (HTA) agencies. For example, HTA agencies in Australia, France and Scotland (5-7) recommend that RCT evidence should be utilised to support assessment for reimbursement, but also note that observational and non-randomised studies may be used to support this evidence. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance for medical device reimbursement in England does not currently state a preference for a particular study design (8). However, the NICE methods and processes for health technology evaluation programmes are being reviewed (consultation ended on the 13th of October 2021) and are expected to place a greater emphasis on RWE (9). This will be discussed further in part two of this blog series.

The currently preferred and permitted evidence types for four countries are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Preferred and permitted study designs for the reimbursement of medical devices

| Country (agency) | Preferred study design | Permitted study designs |

| Australia (MSAC) | RCT | Pseudo-randomised trial, comparative cohort study (concurrent controls, historical or self-control), case series (pre-test/post-test outcomes)

Study designs per NHMRC hierarchy (10) |

| England (NICE) | Not reported | Directly observed clinical outcomes, non-clinical studies (e.g. in vitro), evidence syntheses, modelling studies |

| France (HAS) | Double-blind RCT | Non-randomised or non-blinded trials, patient preference cohort, prospective comparative observational study, propensity score matched cohort

Use of non-randomised study designs must be justified |

| Scotland (SHTG)† | RCT (per IDEAL Framework) |

Lived experiences, RWD, systematic reviews |

†No formalised methods or process guideline was identified; study design requirements have been inferred from published assessments.

Abbreviations: HAS, Haute Autorité de Santé; MSAC, Medical Services Advisory Committee; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RWD, real-world data; SHTG, Scottish Health Technologies Group.

Conclusions

Real-world evidence is increasingly being recognised as a valuable source of evidence for medical interventions and is accepted by a number HTA agencies. Observational cohort studies may have higher external validity than RCTs, increasing the likelihood that results can be extrapolated to the population of interest (1). However, the internal validity is lower, as bias and confounding variables are harder to eliminate (11). Therefore, RWE should be analysed and interpreted with caution (12) and may be most useful in support of RCT evidence. In the assessment of medical devices, RCTs may not always be the most suitable study design, while RWE forms a feasible alternative for evaluation.

If you would like to learn more about systematic literature reviews, please contact Source Health Economics, an independent consultancy specialising in evidence generation, health economics, and communication.

References

- Bondemark L, Ruf S. Randomized controlled trial: the gold standard or an unobtainable fallacy? European Journal of Orthodontics. 2015;37(5):457-61.

- Neugebauer EAM, Rath A, Antoine S-L, Eikermann M, Seidel D, Koenen C, et al. Specific barriers to the conduct of randomised clinical trials on medical devices. Trials. 2017;18(1):427.

- RWE navigator. Real-world evidence. Available at:https://rwe-navigator.eu/use-real-world-evidence/rwe-importance-in-medicine-development/.

- Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized, Controlled Trials, Observational Studies, and the Hierarchy of Research Designs. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(25):1887-92.

- Medical Services Advisory Committee (AU). Guidelines for preparing assessments for the Medical Services Advisory Committee. 2021.

- HAS. Évaluation des dispositifs médicaux – Principes d’évaluation de la CNEDiMTS relatifs aux dispositifs médicaux à usage individuel en vue de leur accès au remboursement. 2019(Available online:https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2017-11/principes_devaluation_de_la_cnedimts-v4-161117.pdf).

- SHTG. What we do. (Available online:https://shtg.scot/what-we-do/).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Medical technologies evaluation programme methods guide 2017 [Available from:https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg33/chapter/introduction.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Review of methods for health technology evaluation programmes: proposals for change 2021 [Available from:https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.nice.org.uk%2FMedia%2FDefault%2FAbout%2Fwhat-we-do%2Four-programmes%2Fnice-guidance%2Fchte-methods-and-processes-consultation%2Fmethods-proposal-paper.docx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK.

- National Health and Medical Research Council (AU). NHMRC levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines. 2009.

- Carlson MD, Morrison RS. Study design, precision, and validity in observational studies. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(1):77-82.

- Ioannidis JPA, Haidich A-B, Pappa M, Pantazis N, Kokori SI, Tektonidou MG, et al. Comparison of Evidence of Treatment Effects in Randomized and Nonrandomized Studies. JAMA. 2001;286(7):821-30.