Written by Paloma Charlesworth (Assistant Project Manager)

Background

Health inequalities are systematic, avoidable, and unjust differences in health outcomes between patient groups. Despite decades of policy and research, they not only persist but in some cases are widening. Over the past decade, the life expectancy gap between England’s most and least deprived areas has increased from 9.1 to 10.5 years among men, and from 6.9 to 8.3 years among women.

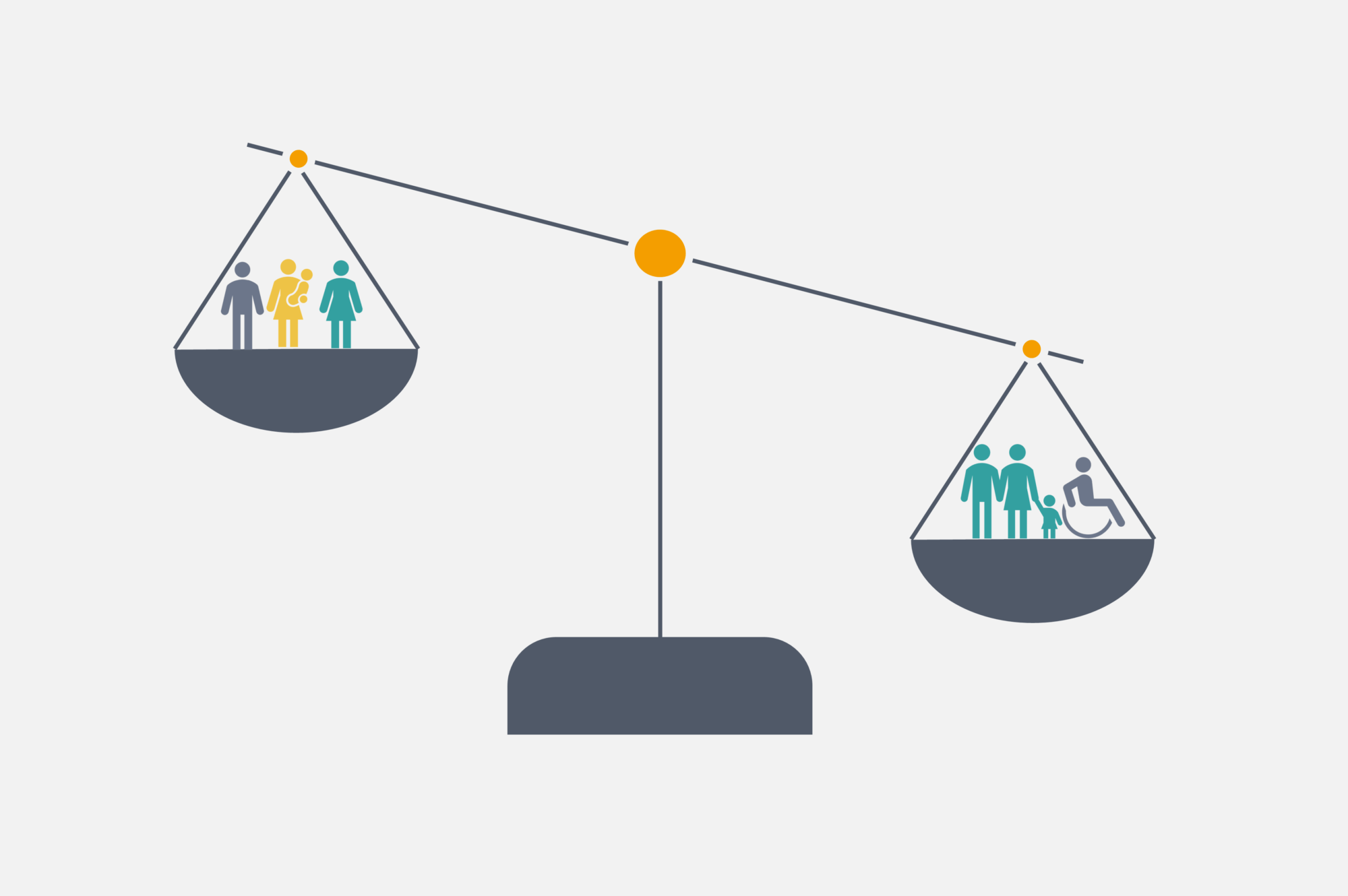

While these inequalities are largely driven by socioeconomic factors, health services play a crucial role in mitigating them. The National Health Service (NHS) has a statutory duty to consider inequalities, making it essential for decision makers to balance overall health gains with efforts to narrow disparities. Central to this balance is how healthcare resources are allocated.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) sits at the heart of these decisions, guiding which technologies and interventions receive funding. Traditionally, NICE relies on cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), which evaluates therapies by their cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). However, inherent to this is the philosophy that all QALYs are to be treated as equal – “a QALY is a QALY”. As a result, in recent years NICE has introduced mechanisms such as disease severity modifiers and higher willingness-to-pay thresholds for Highly Specialised Technologies (HST) – that effectively apply contextual or equity-related weights to QALYs in certain circumstances. However, no comparable adjustments exist to specifically address health inequalities, and NICE’s current approach therefore overlooks how benefits and harms are distributed across different patient groups. As a result, CEA on its own fails to account for how reimbursement decisions have the potential to disproportionately affect already disadvantaged populations.

This conflict between NICE’s stated commitment to reducing inequalities and its reliance on conventional cost-per-QALY methods has long been noted. While longstanding guidance on descriptive methods of reporting health inequalities has offered partial solutions, gaps still remain. For instance, a December 2023 systematic review found that only 42% of Single Technology Appraisals (STA) in NHS England’s CORE20plus5 priority areas mentioned inequalities at all, and where they did, methods were inconsistent and lacked methodological transparency.

To address this, NICE launched a public consultation in January 2025 on proposed updates to its health technology evaluations manual. By May 2025, these changes were implemented, introducing a more structured and transparent approach to considering health inequalities in decision making and utilising the methods of distributional cost-effectiveness analysis (DCEA).

The update

The recent update to NICE’s Health Technology Evaluation Manual, which sets out the framework for manufacturer submissions for reimbursement, provides revised, clearer, and more detailed guidance on:

-

- When evidence on health inequalities should be included

- The types of evidence to submit

- How NICE will use this evidence.

These are discussed in more detail below.

When evidence on health inequalities should be included

-

- Companies should be engaging with NICE as early as possible in the health technology assessment (HTA) process, from NICE early advice to the scoping stage of a HTA, to determine the relevance of health inequalities to a technology.

- Relevance will be judged by:

– The scale of existing inequalities in the patient population

– The size of the expected impact

– The level of uncertainty in the analysis. - Committees will only consider quantitative evidence where the expected effects are proportionately meaningful.

The type of evidence to submit

-

- The primary method is DCEA, which estimates incremental costs and outcomes by social subgroup, scaled to the population, and explicitly accounts for opportunity costs.

- DCEA should be used only as supplementary analysis to CEA, which should also be presented as a stand-alone analysis to allow decision makers to understand the equity-efficiency trade off.

- DCEA requires more detailed data, including parameters disaggregated by social characteristics and disease prevalence. NICE reference case specifies stratifying groups by the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), which generally provides the best data availability.

- Uptake should be assumed equal across groups unless robust evidence indicates otherwise, or where the technology is expected to improve access or adherence.

- For opportunity cost, committees should apply a flat gradient in base-case analysis but also test light and moderate gradients to reflect higher costs in more disadvantaged groups.

- Full probabilistic sensitivity analysis is not required, but deterministic sensitivity analyses should test key uncertainties such as disease prevalence and distribution of health benefits.

- NICE have stated that they will not accept social welfare-based measures, such as the Atkinson Index, as is often used in DCEAs, to apply QALY aversion weights. All QALYs must remain unweighted.

- Outputs must report the following for each IMD quintile:

– Total health benefit

– Health opportunity cost

– Net health benefit (in QALYs)

– Descriptive inequality measures such as gaps, ratios, or regression results. - The strongest submissions will accompany DCEA with a qualitative account of the health equity benefit of a technology.

How NICE will use this evidence

-

- Committees will assess the relevance of health inequality impacts. Where substantial reductions are demonstrated, they may apply flexibility to the cost-effectiveness threshold.

- Recommendations cannot be optimised for subgroups defined solely by social characteristics.

- Higher levels of evidence uncertainty may be tolerated where structural or social barriers to data collection are clearly demonstrated. Committees will recognise such limitations when forming recommendations.

- Presenting total health benefit, opportunity cost, and net health benefit by IMD quintile will allow committees to make more deliberative judgments on the added value of reducing health inequalities.

Anticipated challenges of DCEA

Challenges in conducting DCEAs arise primarily from the greater data demands compared with standard CEAs. Whereas a conventional CEA can rely on population-level averages, a DCEA requires data to be disaggregated by social groups to assess equity impacts.

NICE currently recommends stratification by IMD, but this may not always be appropriate. For example, if inequalities are concentrated in specific social groups (such as ethnic minorities or people with particular health conditions), alternative stratification approaches may be more relevant. However, robust evidence is needed to justify these alternatives, and such evidence is not always readily available.

The standard assumption taken by NICE is equivalent uptake across interventions; however, this may not always be appropriate, and further complexity arises when health inequalities are driven by differences in access to care. In these cases, additional data are required to capture variation in uptake and to inform realistic assumptions about how interventions will be adopted across patient groups.

The evidence requirements also differ by the type of DCEA conducted:

-

- A full DCEA incorporates equity considerations throughout the modelling process, relying heavily on subgroup-specific data. Subgroup specific data may not always be readily available for all subgroups and evidence gaps could increase uncertainty and hence make undertaking a full DCEA more challenging.

- An aggregate DCEA, by contrast, is applied after a standard CEA has been completed. It estimates the distribution of health outcomes across subgroups using aggregate data and therefore requires less detailed subgroup-specific evidence. Although requiring less data an aggregate DCEA is limited in that it may not be able to convey the full impact of an intervention on health inequalities.

The decision of whether to undertake a full or aggregate DCEA may be driven by the available data. Given the additional data requirements and resulting resource investment involved in undertaking a full DCEA, consideration should also be given to the impact that the intervention is likely to have on health inequalities and whether it is likely to be of interest to a HTA body such as NICE to see a full DCEA.

Beyond data considerations, there are also strategic considerations that need to be made before submitting to a HTA body. From a UK perspective, while there is a growing emphasis being put on health inequalities by NICE, there is no universal requirement to provide evidence on the distributional cost-effectiveness of an intervention. Failing to provide this evidence may be seen as a missed opportunity, but manufacturers will need to balance any potential decision-making benefits against the risks of increasing uncertainty arising from incomplete or weak data.

Implications for companies and next steps

The inclusion of DCEA in NICE’S modular update creates new opportunities for companies to strengthen their submissions. By requiring clearer and more formal consideration of health inequalities, NICE has opened a pathway for companies to demonstrate the broader societal value of their technologies where therapies target clinical areas with large inequalities.

To make the most of this opportunity, companies should engage with NICE early to establish the relevance of DCEA. Integrating inequality considerations into strategic planning from the outset ensures that evidence generation addresses the right questions and minimises the risk of costly data gaps later in the process.

We specialise in embedding these considerations into HTA strategies. Our experienced team can provide expert support to ensure your submissions align with NICE’s evolving requirements and fully reflect the value of your technologies. If you would like to learn more about our HTA submissions (including economic modelling) please contact us at Source Health Economics, a HEOR consultancy specialising in evidence generation, health economics, and communication.