Written by Jenna Stephens (and Neil Webb (Head of Systematic Review)

Evidence-based medicine and its standard practice

When Archibald Cochrane formulated his vision for evidence-based medicine (EBM), it was driven by an absence of reliable, robust evidence supporting frequently accepted medical interventions. His observations provoked meticulous evaluations of novel interventions, which subsequently emphasised the need for high-quality evidence in medicine (1). Today, EBM has defined modern medicine; its goal is to minimise the uncertainties in clinical decision-making (2) and to increase the use of high-quality evidence. In practice, this involves the integration of clinical expertise and patient values with the best available evidence (3). As illustrated in the figure above, EBM ranks different types of clinical evidence according to the risk of various biases which may hinder their quality, creating a hierarchical system. For example, observational studies are considered to have a higher risk of bias than randomised controlled trials (RCTs); and systematic literature reviews (SLRs) and meta-analyses provide the most robust and reliable forms of evidence.

The COVID-19 pandemic

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic on 11th March 2020 by the World Health Organization (WHO) (5). As of 20th August 2020, there have been 22,256,220 confirmed cases of COVID-19 reported and 782,456 deaths (6).

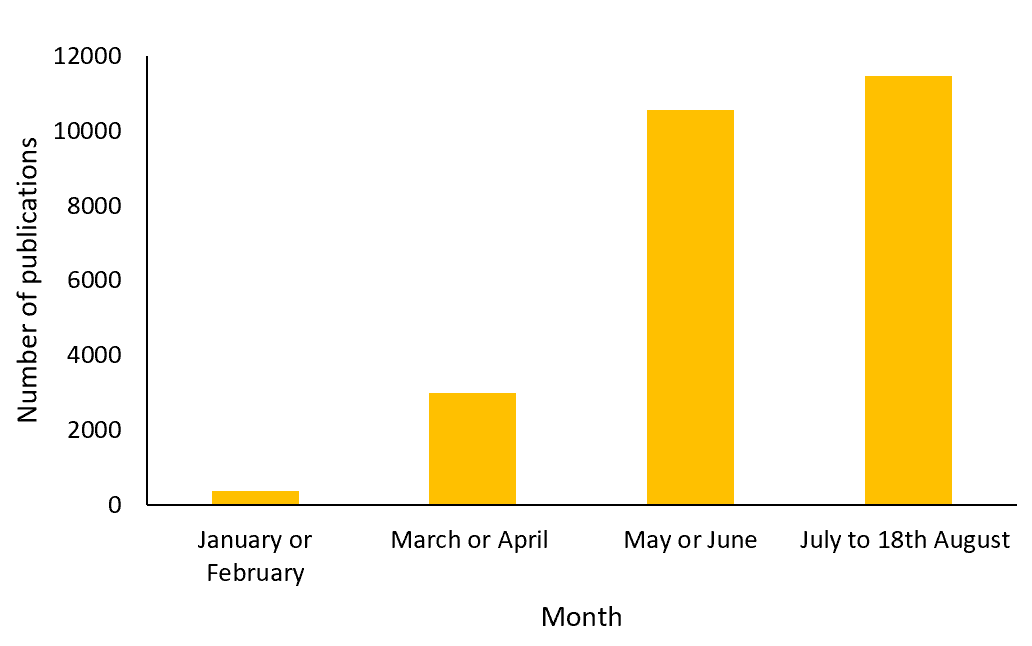

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) issued a statement on the 16th March 2020 regarding the prioritisation of nationally sponsored COVID-19 research, urging all sectors within scientific research to contribute at pace (7). As efforts switched to combat the pandemic, a sharp increase in COVID-19-focused research was observed. The figure below illustrates the sudden increase in literature referencing COVID-19 in 2020 registered in the Medline database, from 379 publications in January or February to 10,548 publications in May or June.

The number of publications referencing COVID-19 in the Medline database in 2020

Despite the rapid increase in COVID-19-related research, high-quality RCT evidence is limited, with other sources of evidence more readily available (8). This trend is a response to the significant pressure to find existing or novel treatments and/or develop a vaccine for COVID-19 to combat the current global public-health emergency.

In response, key agencies within the UK and Europe have introduced changes to their standard processes for producing evidence guidelines, and the evaluation of medical products and regulation. A summary of updated guidance from a few UK- and European-based agencies are discussed below.

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

NICE has adapted its recommendation process, following previously published methods for guidelines developed in response to health and social care emergencies (9). Utilisation of available evidence is a top priority.

The lack of RCT data has necessitated steps to ensure the quality and validity of other sources of evidence, for example real-world data, which has been used to inform COVID-19 NICE guidance (8). A critical appraisal of evidence, including a risk of bias assessment is required, based on a suitable checklist. For example, the Newcastle-Ottawa scale and the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) checklist are recommended for appraising non-randomised studies and qualitative studies, respectively (8).

In health and social care emergencies, the speed with which NICE examine evidence and publish guidelines related to the emergency is also expedited. Some stages of development may be undertaken iteratively or in parallel (9). The guideline imposes trade-offs for shortening, omitting, or accelerating the process and methods for developing NICE guidelines (9). Additionally, early in the pandemic, NICE prioritised therapeutically critical COVID-19 topics (10).

As well as producing rapid guidelines, NICE have been working with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to rapidly review the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 treatments to produce an evidence summary (10). For example, NICE have produced a rapid review of remdesivir based on two RCTs (including a meta-analysis of the two) and one observational study, which demonstrated a potential clinical benefit in COVID-19 patients (11). The rapid evidence summary highlights key information regarding the appropriate use of remdesivir in clinical practice, which may be pivotal in the treatment COVID-19 within the National Health Service (NHS).

European Medicines Agency (EMA)

Remdesivir is the first COVID-19 treatment intervention recommended by the EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) for a conditional marketing authorisation (12). The European Commission fast-tracked the decision-making process and granted conditional marketing authorisation in July, less than a month after it was submitted (13). The conditional marketing authorisation facilitates early access to medicines within the EU, based on the assessment of less comprehensive data than normally required (14). In April 2020, for part of this assessment, the CHMP commenced a rolling review of remdesivir (15).

Before the pandemic, a market authorisation application was completed with all the supporting data available at the beginning of the evaluation process. However, during public health emergencies, rolling reviews enable faster evaluation of promising medicines, in which the agency will review data as it becomes available. This enables the review process to be completed in a shorter time frame.

Pandemic conditions may also encourage the ‘compassionate use’ of medicines. This enables unauthorised medicines in development to be prescribed to patients with no other treatment options or who cannot enter clinical trials (16).

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)

To provide support during the COVID-19 crisis, the MHRA has introduced flexibility in their regulation process (e.g. good manufacturing practice [GMP] and good distribution practice [GDP]), in order to advance the supply of key healthcare products and the wider pandemic response within the UK (17). The first COVID-19 intervention to receive positive scientific opinion by the MHRA using the more flexible regulation process was remdesivir (18).

Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC)

The SMC has responded to the pandemic by adapting their usual procedures (19). New submissions or resubmissions are no longer being accepted in order to free up availability of staff to support activities relating to the pandemic. New submissions relating to COVID-19 are the priority.

Conclusion

The public health emergency resulting from COVID-19 has paved the way for novel, expedited methodologies for the approval of medicines and health technologies. Accepted practices for EBM are currently unfeasible, which has meant medical agencies across the UK and Europe have had to adapt their processes.

The limited availability of high-quality RCTs and long-term outcomes data has led to a reliance on observational data, which reduces confidence in outcomes due to the inherent high risk of bias in such studies. In addition, there is pressure to expedite decision making to ensure rapid access to treatments or vaccines for COVID-19. In this scenario, it is essential to adapt processes and methods whilst ensuring as much rigour as possible before normal EBM can be resumed.

References:

- Cochrane A. Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random Reflections of Health Services: Nuffield Trust; 1971.

- Shah H, Chung K. Archie Cochrane and his vision for evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(3):982-8.

- Masic I, Miokovic M, Muhamedagic B. Evidence based medicine – new approaches and challenges. Acta Inform Med,. 2008;16(4):219-25.

- Novella S. Responding to SBM critics. 2017. Available at: https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/responding-to-sbm-critics/.

- Archived: WHO Timeline – COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-04-2020-who-timeline—covid-19.

- WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2020. Available at: https://covid19.who.int/.

- NIHR. DHSC issues guidance on the impact of COVID-19 on research funded or supported by NIHR. 2020. Available at: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/news/dhsc-issues-guidance-on-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-research-funded-or-supported-by-nihr/24469.2020.

- NICE. Assessing the quality of wider sources of data and evidence in our guidance on COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/covid-19/assessing-the-quality-of-wider-sources-of-data-and-evidence-in-our-guidance-on-covid-19.

- NICE. Developing NICE guidelines: the manual. Process and methods [PMG20]. Updated 17th July 2020. Appendix L: Interim process and methods for guidelines developed in response to health and social care emergencies. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/resources/appendix-l-interim-process-and-methods-for-guidelines-developed-in-response-to-health-and-social-care-emergencies-8779776589/chapter/health-and-social-care-emergency-guideline-recommendations.

- NICE. Our approach to COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/covid-19.

- NICE. COVID 19 rapid evidence summary: Remdesivir for treating hospitalised patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. Evidence summary [ES27]. 2020. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/es27/chapter/Key-messages. .

- EMA. First COVID-19 treatment recommended for EU authorisation. 2020. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/first-covid-19-treatment-recommended-eu-authorisation.

- European Comission. European Commission secures EU access to Remdesivir for treatment of COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1416.

- EMA glossary: conditional marketing authorisation. 2020. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/glossary/conditional-marketing-authorisation.

- EMA starts rolling review of remdesivir for COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-starts-rolling-review-remdesivir-covid-19.

- EMA glossary: compassionate use. 2020. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/glossary/compassionate-use.

- MHRA regulatory flexibilities resulting from coronavirus (COVID-19). 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/mhra-regulatory-flexibilities-resulting-from-coronavirus-covid-19.

- MHRA issues a scientific opinion for the first medicine to treat COVID-19 in the UK. 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/mhra-supports-the-use-of-remdesivir-as-the-first-medicine-to-treat-covid-19-in-the-uk.

- SMC response to COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/about-us/latest-updates/smc-response-to-covid-19/.